The EU Clean Aviation research and technology project is striving to meet ambitious sustainability targets against an equally exacting timeline, but industry players are prioritizing new technologies that improve short-term competitiveness. Although the public recognizes the fast-changing economic and geopolitical environment, aviation may face a credibility challenge.

European civil aviation needs to adjust its approach to achieving its sustainability goals. Some major players have postponed breakthrough technology projects in hydrogen and hybrid-electric propulsion, while others continue to emphasize their relevance.

- EASA executive director sends a wake-up call on certification timeline

- Despite Airbus’ delay, hydrogen remains at the center of debates

The EU’s Clean Aviation public-private partnership has aimed to demonstrate technologies for cutting greenhouse gas emissions at the aircraft level by 30% compared with 2020 technology. The program’s goals include service entry in 2035, a timeline that would enable the new aircraft to replace 75% of the existing civil fleet by 2050.

For those next-generation products using Clean Aviation technologies to receive certification, airframers and engine-makers should apply by 2029, European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) Executive Director Florian Guillermet said at the Clean Aviation Annual Forum held in Brussels March 18-19.

Guillermet’s wake-up call emerges as Airbus has postponed its ZEROe hydrogen aircraft project, which would have contributed to meeting the total emissions target by 5-10 years. The airframer is still working on an A320 short-to-medium-range replacement but has deferred service entry to the second half of the next decade. At the same time, Clean Aviation officials are insisting on the 2035 deadline, and Guillermet’s comments have added significant pressure.

“In 2028, there will be a reality check,” he said. “At that time, we will have to see you knocking at EASA’s door [and applying] for the type certificates of your new products. At least, we need the assurance we will have the applications by 2029.”

A 2030 deadline could be acceptable in Guillermet’s view, but such a slip would rely on a shorter certification cycle. EASA is participating in Clean Aviation’s Concerto project, under which the cycle would be expedited to six or even five years from the usual eight.

Guillermet stressed that the story of new fuels, more efficient operations and greener technologies “has to come together and walk the talk, otherwise we will not be credible.”

Airbus is focusing on a “realpolitik” approach to accelerating innovation of products in the nearer term. “Technological breakthroughs alone are not enough,” Chief Technology Officer Sabine Klauke said. “Industry must also ensure that innovation is adopted at scale, and that it is economically viable and fully integrated into the aviation ecosystem. Securing the uptake of innovation for the next generation of aircraft is not just about technological breakthroughs. Even if this is sometimes already difficult enough, it is about making innovation a reality in our products.”

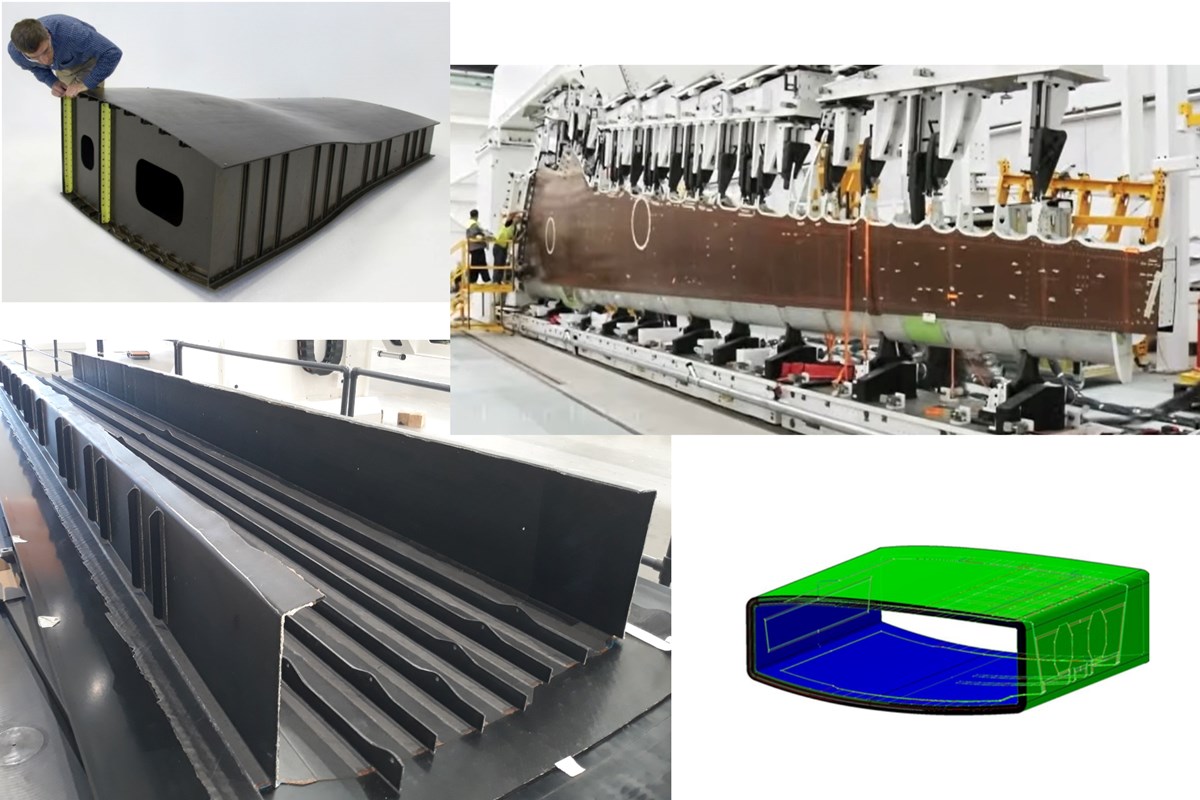

To help accelerate technology maturity and scalability, Klauke said much attention needs to be paid to certification and industrialization as to the technology itself. Citing the recently completed Multi Functional Fuselage Demonstrator (MFFD), she said that by paying equal attention to all aspects—including certification and manufacturing—the MFFD can make “a significant contribution to achieving the goals of future high-rate production and sustainable flight.”

Launched in 2014 under the Clean Sky 2 research program’s Large Passenger Aircraft effort, the MFFD is an 8-m-long (26.2-ft.) and 4-m-dia. section of an A320-size fuselage produced largely from thermoplastic composites. Its construction uses multiple alternative forming and joining technologies, with the goal of reducing weight and recurring costs while enabling high-rate production.

Resulting in up to 10% lower structural weight, MFFD technologies could translate into as much as 540 kg. (1,190 lb.) in lower CO2 emissions per flight.

Affordability is also key to accelerating the installation of new technologies into the fleet—and hydrogen has yet to achieve that, according to Airbus. To earn their way onto new aircraft, Klauke said technologies “must be designed for cost-effective production, maintenance and life-cycle management.” New propulsion systems and fuels, be they sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) or hydrogen, “must reach cost parity with conventional fuels,” she said. “The volume of production of these energies must also be consistent with the size of the commercial aviation market, and this production must be environmentally sustainable.

“The whole chain needs to play, and this requires investment in infrastructures, incentives and policy frameworks to create a viable market,” she added.

International competition is intensifying, Klauke warned, so Europe cannot “sit on our laurels” and must secure its advantageous position while it still can. “Europe must act strategically to create a level playing field for decarbonization,” she stressed. “While innovation must drive environmental sustainability, it must not create competitive disadvantages for the European industry.”

Ensuring access to critical resources will be key. “The future of aviation depends on secure, sustainable supply chains of materials, batteries, SAF, hydrogen, just to name a few,” Klauke said. “Industry and governments must work together to guarantee supply, security and sovereignty. Europe must continue to leverage the benefits of public-private partnerships programs to remain a leader in the aviation sector.”

Other forum attendees urged the importance of maintaining hydrogen-related propulsion research as a key strategic goal and emphasized that Airbus’ recent decision to postpone development of a hydrogen-powered airliner should not impede or discourage continuing research into hydrogen use in the medium or long term.

Airports should continue to prepare for the introduction of hydrogen-powered aircraft, Airports Council International Europe President Armando Brunini said March 18.

Air transport is counting on SAF as the main contributor to net-zero CO2 emissions. “Nevertheless, we need hydrogen,” Brunini said. “SAF will not do it alone. We also need new-technology aircraft to reach net zero. We should not stop because of a 5-10-year delay. . . . Let’s not relax, otherwise we will fall into a vicious circle, and airframers will blame a lagging infrastructure again.”

Brunini is also CEO of SEA Milan Airports, and he noted that Milan Malpensa Airport is working on four hydrogen-related research and technology projects.

Questions about hydrogen’s place in aviation’s net-zero emissions agenda come as officials are discussing funding priorities for Europe’s next Framework Program for Research and Innovation, FP10, which will begin in 2028.

“We’ve got to keep developing that pipeline,” said Alan Newby, Rolls-Royce’s director of aerospace technology and future programs. “We are now benefiting from programs we kicked off, in some cases in Clean Sky 1 or Clean Sky 2, so we need FP10 to start developing those next ones. While hydrogen may not be available to mainstream aviation by 2035, that doesn’t mean we should stop doing [the research]. The environmental and economic case is very strong. So we need to keep pushing that through these programs, such that when we get to the next generation we are ready.”

Newby acknowledged the importance of improvements in overall gas turbine efficiency and adoption of sustainable aviation fuel to delivering near-term reductions in emissions, “but that doesn’t mean saying we should stop investing in the long-term technologies as well,” he said.

FP10 is planned to safeguard European sovereignty, competitiveness and sustainability. “I think for us, the world doesn’t stop at 2035,” Newby said. “We’ve got to make sure we’re delivering those programs and bringing value into Europe as well. We’ve got massive assets in the European aviation industry, and we lose interest at our peril. So we’ve got to keep investing in our next-generation technologies, which will keep us ahead of our competitors.”

Clean Aviation itself omitted hydrogen from its third call for projects, released in December, with the first for Phase 2 beginning in 2026. Having funded multiple projects in Phase 1, Clean Aviation is officially planned to invite bids for hydrogen projects in later calls, but that could change.

However, progress continues in the program’s hydrogen efforts. Rolls-Royce is involved in Cavendish (Consortium for the Advent of Aeroengine Demonstration and Aircraft Integration Strategy with Hydrogen), a €29.2 million ($31.6 million) project targeting integration of liquid hydrogen systems into a ground-test engine and definition of requirements to move toward flight demonstration.

This year’s Clean Aviation forum also involved more startups amid a recognition that small innovator companies are often better positioned to accelerate the introduction of new technology than traditional manufacturers. During a panel discussion at the event, Val Miftakhov, CEO of hydrogen-electric propulsion developer ZeroAvia, said his company’s approach is “just to start doing it.”

“We’re scaring ourselves with the complexity of the task to move the entire industry over,” Miftakhov said, referring to the big-picture goal of transitioning aviation to hydrogen. “But the reality is, as in any big journey, it starts with the first step, and the first several steps in the first mile and so forth. You start doing things—that’s how you get to the finish line faster. If you just keep thinking about starting the race, then it will take you longer to get there.”

ZeroAvia is therefore focused on the development and certification of its first practical 600-kW electric propulsion system for its initial ZA600 powertrain as well as the associated fuel-cell power-generation system.

“That’s how we’re going to get started, and that’s how we’re going to persuade everybody that this is a viable path to take,” Miftakhov said. “So that’s why we are taking very decisive steps—the first of which is a Part 23 small aircraft[Cessna Caravan] already in commercial service.

“Everybody is, of course, telling us our timelines are aggressive, but that crystallizes everybody around the test,” he continued. “We actually come to the regulators with the actual hardware, and we say, ‘We want to certify it. Here it is. Here’s how we propose to certify it.’ So these are not theoretical conversations, and that’s how you energize everybody—and then the tangible things happen.”

Clean Aviation has taken a different but converging approach with the Dassault Aviation-led Concerto project, which focuses on expediting certification of new technologies. For future so-called active wings, engineers are relying on test models both to advance knowledge in canceling vibration and to find new means of compliance with certification principles.

As future aircraft may have higher-aspect-ratio wings, they could be more prone to flutter and thus need a control system to prevent the structural vibration that could break the wing. Experimental Validation Aircraft (EVA) models will be used to demonstrate flutter suppression through additional moving surfaces while serving as a platform to evolve EASA rules, which currently do not allow flutter control. The EVA demonstrators will produce a concept of operations and gap analysis versus the EASA CS-25 certification rules for transport aircraft, then draft regulatory material to address the identified gaps, Clean Aviation Project Officer Jaime Perez de Diego said.

The first EVA model underwent ground testing in French national aerospace research center Onera’s wind tunnel in Lille; a second model is slated for flight testing next year, by which time Concerto participants aim to reach Certification Readiness (CRL) Level 4, meaning they will establish a road map for rulemaking. EASA introduced the nine-stage CRL scale in 2024 to close the gap between a technology’s maturity and its ability to comply with certification rules.

www.assemblymag.com

www.assemblymag.com

www.assemblymag.com

www.assemblymag.com